On average, over 45,000 aircraft take off across the United States, carrying over 2.9 million passengers to destinations across the country, connecting them to friends, family, and business opportunities. Combined, these daily flights require over 157,500,000 gallons of jet fuel each day, and that is just in the United States.

Air travel is booming too. Unlike the early days of travel, new low-cost carriers are helping people of all socioeconomic standing see the United States and the world. Estimates show that the number of passengers will double over the next twenty years.

This doubling of passengers is what led the International Energy Agency to predict that aviation will account for 15 percent of global oil demand growth over the next decade. Think about it. The average jet fills up with 3,500 gallons of jet fuel, which can cost upwards of $11,690.

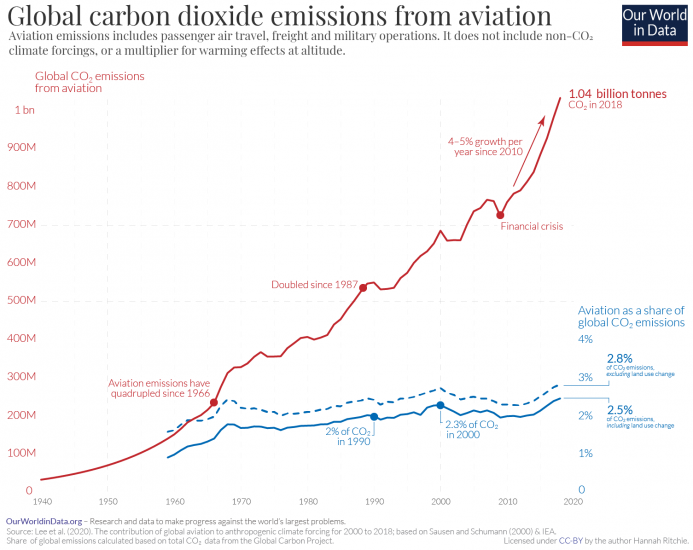

All that fuel has to be burned emitting carbon dioxide as you fly. In 2018, it is estimated that global aviation – which includes both passenger and freight – emitted 1.04 billion tons of CO2. This represented 2.4% of total global CO2 emissions in 2018, according to the Environmental and Energy Study Institute. In their issue brief, they said that percentage is expected to triple as passenger travel and freight travel increase into 2050.

With the fluctuating price of jet fuel, supply constraints, and concerns over the industry’s environmental footprint, airlines worldwide are looking for ways to become more fuel-efficient and eco-friendly. This is why U.S. airlines have improved fuel efficiency by over 135 percent since the 1970s. Becoming more fuel-efficient not only allowed many more people to afford airline tickets but also substantially reduced CO2 emissions.

Yet, despite these efficiency improvements, airlines worldwide are still looking for ways to increase the sustainability of their operations instead of just having more fuel-efficient planes and routes.

So what are they looking at? Sustainable aviation fuel.

Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is a variety of different types of jet fuel. Some ideas suggest using less crude oil through blending and others propose no crude oil at all to lift jets into the sky. As a result of all these options, some refiners are using waste fat and grease from restaurants, while other refiners are focusing on dried biomass from corn, algae, or jatropha – a shrub or small tree that grows in Central and South America.

While there is a lot of research and testing, the Biden Administration hopes to accelerate the process by calling for 3 billion gallons of sustainable aviation fuel to be produced by 2030. The largest focal point – and optimism – for biofuel resides in America’s Heartland, where large amounts of low-cost ethanol can be produced.

Even as the airline industry looks to sustainable fuel to reduce their CO2 emissions, the companies that will need to produce sustainable aviation fuel have their own emissions to deal with. For example, average ethanol plants producing biofuel today emit 150,000 metric tons of CO2 annually. Although research continues into the plants and processes utilized to produce biofuel with fewer emissions, the fact remains that increasing our reliance on these facilities for 3 billion more gallons of fuel each year will only lead to growing CO2 emissions.

With jet fuel representing 20%-30% of airlines operating costs, the price of SAF will be a major consideration for pricing tickets. While the urgency to develop SAF is critical, no alternative fuel is approved at more than 50% blending with conventional fuel, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. That means, in the near term, we will need to continue to address the issues of emissions that we have solutions for now.

Because of this blending wall, enhanced oil recovery using carbon capture is one of the best options for reducing CO2 out of the air. Capturing carbon and using it for enhanced oil recovery accomplishes three key goals for sustaining our environment, as noted by the International Greenhouse Gas protocols. First, the EOR process results in safe, long-term storage underground preventing CO2 from entering our atmosphere. Secondly, the use of CO2, along with enhanced oil recovery, allows for existing oil wells to be utilized more efficiently – creating energy security while keeping the environmental footprint of their operations to a minimum. Lastly, and most important, CO2 and EOR using industrially captured carbon produces oil that is net-negative in carbon emissions.

Not only would this allow blended jet fuel to be net-negative, but the processing plants would also be net-negative and airlines could capitalize on fewer variations in fuel prices. Overall, these solutions help mitigate emissions and answer the question of how when we need them most.

Fortunately, industry leaders have already acknowledged this simple fact. And these leaders believe carbon capture is the solution.