By David Holt, President of Consumer Energy Alliance

We are pleased to be able to engage in a thoughtful conversation about Low-Carbon Fuel Standards (LCFS), because, until now, there really hasn’t been enough discussion about an this issue that will impact so many.

That’s been true even as LCFS supporters are leading aggressive campaigns in more than 20 separate states – each aimed at imposing this mandate on a state or regional basis, and then drawing on that momentum to demand its implementation nationwide. All the while, there has been very little substantive discussion on how this “energy” initiative will affect fuel prices, the lives of consumers and the consequences it will have on our ability to import secure, affordable energy from Canada.

As we wrote on our blog last week, NRDC’s engagement on this issue is a welcome development – and one we hope will lead to a more constructive debate (or at least: some debate at all) on the real-world consequences associated with an LCFS. Some LCFS proponents continue to mistakenly claim that an LCFS will actually produce a chemical change in the carbon content of the fuels we use. To its credit, and as point on which we can agree, NRDC doesn’t seem to support this notion. That said, some of NRDC’s statements indicate a misunderstanding of the basic mechanics of how an LCFS would actually work. And who would be forced to pick up the bill for the increased fuel costs that will accompany their implementation.

On these issues, though, CEA can provide some meaningful assistance. Below we take a look at NRDC’s most recent posting on the LCFS and the Canadian oil sands, and humbly offer a few key corrections where needed.

NRDC says: “[T]he reality is that the LCFS starts to wean us from the choke-hold that oil has on today’s transportation and will help us gradually transition to more diverse, cleaner choices for fueling our mobility.”

The reality is: Under an LCFS regime, the amount of energy imported each day that’s needed to fuel our cars, trucks and minivans wouldn’t necessarily change – but the places from which those resources come (and the amounts provided by each) would certainly see a dramatic shift.

Implementing a policy that has a direct consequence of preventing Canadian and Mexican energy from crossing the U.S. border will create a significant short-term vacuum, to be sure – but one that suppliers from the Middle East, Africa and the Far East will be more than happy to fill. You see, under the accounting methodology of the LCFS, oil originating from unstable regions half-a-word away generally receives a better carbon score than energy resources produced in Canada, Mexico and even the U.S. Intermountain West – even though these resources bear carbon profiles that are chemically identical to crudes from far-away lands.

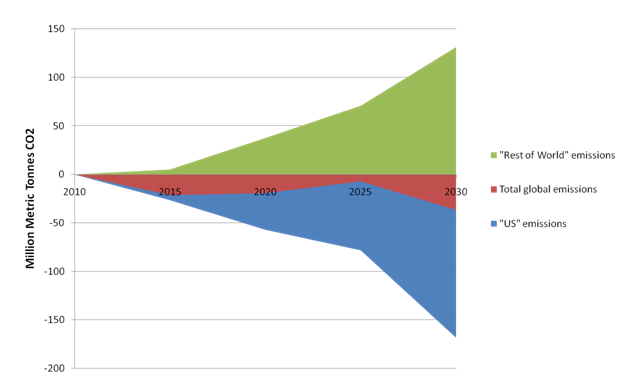

Maybe that’s why study after study has shown that an LCFS may actually increase global emissions of carbon dioxide, not reduce them. Remember: Foreign crude doesn’t arrive in U.S. refining centers via teleportation. It has to travel more than 12,000 miles before it gets here. Remarkably, the LCFS scoring mechanism doesn’t seem to account for those emissions – but those who know the issue best certainly do. Just ask the U.S. Department of Energy’s top energy policy analyst. This slide, we think, is particularly relevant to this question:

A more direct approach calling for the long-term diversification of our transportation fuel mixture must be considered and would be a better approach than an LCFS. We will simply not be able to convert enough vehicles in the near-term to alternatives to meaningfully reduce imports. The infrastructure, technical know-how and alternative fuel availability simply do not exist today. Hoping that alternative energy can & will make a significant difference today does not make it a reality. We need to diversify our energy resources and we need to start now so that in 40 or 50 years alternative energy will actually make a meaningful contribution.

NRDC says: “The low carbon fuel standard is expected to reduce our fuel costs by making America more fuel efficient and by providing alternatives to our oil dependency.” (emphasis theirs)

The reality is: The truth is, an LCFS is not designed to improve fuel economy or efficiency – precisely because it has nothing to do with the fuel in your gas tank – and will actually raise our fuel costs substantially.

How is that so? For starters, it’s important to understand first what an LCFS actually seeks to regulate. It regulates the production of oil. It regulates the transportation of it. It regulates the refining of it. And it regulates the distribution. The only thing it doesn’t regulate, in fact, is the combustion of that fuel in your gas tank – which, incidentally, happens to account for 80 percent of CO2 emissions that come from the transportation sector.

We’ll repeat that: The LCFS doesn’t even attempt to address the source of more than 80 percent of carbon emissions that arise from the transportation sector. But that doesn’t mean that an LCFS would let American consumers off cheap. Far-away oil may receive a better score under the LCFS accounting regime, but it also happens to be a lot more expensive to buy than the secure, affordable energy resources available to us closer to home. According to one study published recently in the American Economic Journal, the price you pay at the pump could jump $0.60 a gallon under the best case scenario.

NRDC says: “The low carbon fuel standard will … help us protect our precious North American environment, improve the health of communities already living with too much pollution, and reduce the need to commit U.S. troops in unstable, oil rich areas of the world.”

The reality is: An LCFS regime would actually prevent sources of secure, reliable energy from crossing the border, thereby creating the circumstances that will allow sources of far-away, unstable, and expensive energy to increase its share of the U.S. market. In other words, the clear, direct consequence of an LCFS is to reduce Canadian imports, as well as production of crude in parts of the United States.

As far as NRDC’s suggestion that an LCFS would “protect our precious North American environment,” here we have another assertion that simply isn’t grounded in the facts. The truth is, Canada’s oil sands are found beneath 140,000 square kilometers of land in Canada – part of a forest that’s more than 3.2 million square kilometers in size. Here’s the kicker: Of those 3.2 million square kilometers, only 4,802 of them are actually mined – and every square inch of that is required by the government to be fully reclaimed, returning the land to a sustainable landscape equal to its condition prior to development. Further, preventing imports of fuel derived from the Canadian oil sands into the US will not prevent development of these resources – they will simply be developed and sold into other overseas markets.

NRDC says: “Policies like the LCFS will help make the U.S. more competitive by encouraging the use of more sustainable resources and complement the creation of millions of clean energy jobs under new climate policies.”

The reality is: It may indeed be true that an LCFS will someday help create new jobs – but no one can credibly claim that those jobs would be based in the United States. More realistically, an LCFS will spur job creation and economic development in the regions of the producing world that stand to win under the system (the Middle East), and achieve roughly the same effect for regions of the consuming world that stand to claim secure and affordable energy resources from Canada that, without an LCFS, would have been sent to the United States instead (Asia).

But what would happen to this country? Fuel prices would be rendered prohibitively expensive. Our dependence on foreign, unstable oil would go even higher. And thousands of jobs would likely be lost – all sectors of the U.S. economy – or, at least, all sectors that require affordable and reliable sources of fuel to remain in operation.

NRDC says: “While CEA claims that Wall Street will be enriched at the expense of Main Street, we don’t expect Wall Street to be involved in [the LCFS] credit market.”

The reality is: One of the least talked-about elements of the LCFS is the credit trading scheme that the implementation of such a policy would necessarily create. NRDC’s suggestion that it doesn’t “expect” LCFS credits to be bought and sold on the open trading market shows a lack of full understanding of LCFS regimes in the best case, and downright disingenuous in the worst – especially when considered in the context of the effort’s broader (and stated) goal, which is to force an LCFS to be imposed nationwide.

So there you have it: For those interested in having a genuine, substantive debate on the LCFS and its potential impact on American energy consumers, U.S. energy security and efforts to rejuvenate U.S. job creation, consider this an invitation to join an open, honest debate.