Supply chains have always been vital, fragile things. In 2020, Americans learned firsthand during the pandemic how complications and stresses on international supply chains hit home when supplies of toilet paper, meat, and even lumber came to a screeching halt during the COVID-19 pandemic. We all watched as the series of steps necessary to go from raw materials to manufacturing and to delivered products to consumers broke down worldwide.

As an example, medicinal compounds are high value. A pharmaceutical supply chain could start in a farmer’s field in Asia, where particular plants naturally produce the needed compounds, which are taken from the plant and turned into a product.

That product is then put on a container ship headed for docks at Long Beach, California. It will be loaded on trucks or trains, moved to a distribution center, then transported to a pharmacy, and finally purchased by a customer. The supply chain for that medicine can be traced from harvesting the seeds used to plant the next crop to the ultimate end user.

Now imagine this supply chain is disrupted.

Perhaps the seeds for the next crop go bad, or the crop gets flooded. Maybe the power goes out in a foreign factory that processes the plants into life-supporting products. Or workers at the Long Beach port go on strike, and the product never gets off the dock.

You get the idea. Supply chains are fragile. Especially during a pandemic when mysterious health problems can shut down large segments of them. Equally delicate are our energy supply chains.

Energy Supply Chains

Like the medicinal example above, consider all the steps necessary to develop oil from raw material all the way to the point when you buy it from a gas station. First, you have to find it. No one posts real estate signs saying, “Drill here.” If the oil deposits are confirmed, equipment is coordinated, rigs are built, and work begins to extract the energy. Once out of the ground, the crude oil is stored en route to a refinery that makes it into gasoline, diesel, jet fuel and other products. When it’s ready, those supplies are then transported onward to commercial, industrial and consumer buyers.

There is an incredible number of steps required to prepare oil for personal automobiles or jet fuel. Each one of those steps – identify, explore, build, produce – have their own lengthy and detailed process.

The question is, what’s the best way to move oil to the correct refinery? Refineries are sited and built to process specific kinds of oil. Refineries made to process heavy crude like the kind you get from the Canadian oil sands would require extensive and expensive retrofitting to be able to refine different types of oil.

Now ask yourself, would you rather have an energy supply chain that is safe, secure, and in the same hemisphere; or one that takes time to receive and has a greater risk of causing environmental contamination? Oil transported by tankers from overseas could face similar disruptions to those listed in our theoretical supply chain for medicine originating in Asia.

In Minnesota, Enbridge Line 3 is the cheapest, safest, and environmentally friendly way to deliver oil to refineries. The pipeline is an essential part of that supply chain. Trucks, trains, and ships are not as environmentally friendly as a pipeline, especially as the compressor stations that push products through the pipeline, are starting to use solar energy. And alternative forms of transportation require fuel and are more expensive to use. Do you know who pays for price increases that arise from disrupted supply chains? You do.

Affordability is critical because energy costs hurt those on the lower economic rungs the most. Energy costs are regressive, meaning the less you make, the higher the percentage of what you earn pays for home heating, cooking, and other energy needs. A family surviving on $45,000 annually might devote 10-20% of earnings to energy. A family making $110,000 pays the same amount as the other family. Still, that amount is much less of a percentage of their earnings. Why are we making things even tougher on low-income families during a pandemic?

The need for oil does not go away when pipelines close, and closing pipelines make energy cost more because alternative delivery methods are more expensive. If Line 3 is closed, the demand for oil could require more than 750 tanker trucks a day to compensate for losing the pipeline. That’s at least 30 truckloads an hour on Minnesota roads for 24 hours a day. Does anyone want that traffic on their roads?

The current energy supply chain is simple; it goes from the Canadian Oil Sands through a pipeline to U.S. refineries. By intentionally shutting down Line 3, the process gets infinitely more complex. It could add in new countries if we are forced to rely on foreign exports, with new modes of transportation – including oil tankers, trucks, and rail – and infinitely increases the price and the amount of risk to the environment and the supply chain.

Venezuela, Nigeria, or Canada?

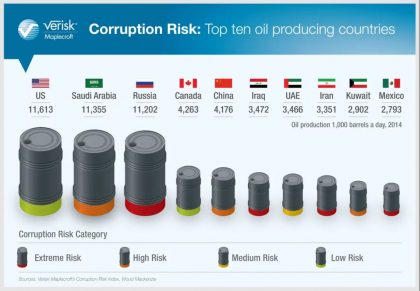

Shutting down Enbridge 3 in the courts might require Minnesota to seek oil from other sources that provide the right kind of oil for Minnesota’s heavy crude refineries. While Canada leads the pack in terms of the amount of oil they can produce, other countries include Venezuela, Nigeria, Russia, China, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Angola. All of these sources require ocean-going shipping, but there are other challenges to consider.

Venezuelans can tell you about supply chains because their basic, subsistence food supply chains are broken. Reports have said that tens of thousands of Venezuelans seek food at the Columbian border. Buying crude from Venezuela means propping up a dictator who abuses the people and doesn’t know how to keep the economy going or allow the market to keep food on the grocery shelves.

Nigeria is rich in natural resources. It has natural gas, tin, iron ore, coal, limestone, lead, zinc, and good farmland in addition to oil. Revenue from petroleum exports might be as high as 86% of total export revenue. You’d think such a country would be a good trading partner. Still, Nigeria has other unresolved issues from political corruption and environmental degradation to human trafficking and piracy (like on boats), making it an unsavory place to do business.

The others have their issues, too, the primary one being that we could be forced to rely on nations that don’t always share our values and commitment to environmentally sound energy production, like Canada.

Instability in places like Venezuela and Nigeria makes them less attractive trading partners. For the U.S., Canada is the more important and dependable trading partner. Why are we intentionally damaging our energy supply chains by shutting pipelines from Canada, like Minnesota’s Line 3?

Advantage: Canada

Canada is America’s biggest trading partner. However, this relationship is critically dependent on supply chains and energy infrastructure.

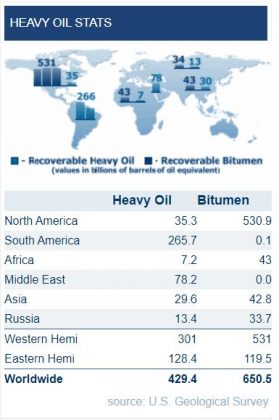

Canada’s energy resources are massive, making it the fourth-largest producer of heavy oil in the world. Of the globe’s oil reserves, nearly 1 out of every 10 barrels are located in Canada. The vast majority of that oil is located in the Oil Sands region, and 98% is exported to the U.S. This helps maintain energy security ties for North America.

Additionally, there are fewer GHG emissions from a barrel of oil derived from the oil sands with each passing year. Since 2000, such emissions have fallen 36% because of cleaner-burning engines. After all, the primary source of GHG is transportation. Pipelines are not only safer; they produce much less GHG than if trucks, trains, or ships transported this oil to the refinery.

Plus, does anyone really think Venezuela, Nigeria, or Russia have the same environmental regulations as the U.S. or Canada? It’s important to know that the most advanced technology and environmental policies have been put in place specifically around extracting and transporting oil. When it comes to our international supply chains’ welfare and safety, the environment, and keeping energy prices low during a pandemic, Minnesotans win with Canadian pipelines safely delivering oil to their refineries.