After receiving nearly $2.5 million dollars from activist groups, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s first act upon taking office in January of 2019 was to take steps to shut down Line 5, regardless of her campaign promise to be a champion for all Michiganders. This action came after a bipartisan law was passed in the Michigan Legislature to create a privately funded tunnel by the pipeline operator burying the segment crossing the Straits that was the concern to virtually eliminate the potential threat to the environment and water quality.

This political activism has stretched into a longer, more complicated problem that ended up triggering our neighbors to the north to invoke a 1977 bilateral treaty, sending the matter into international arbitration. Gov. Whitmer and AG Nessel doubled down, saying similarly that the Line “has imposed on the people of Michigan an unacceptable risk of a catastrophic oil spill in the Great Lakes that could devastate our economy and way of life.”

The unique challenge for Governor Gov. Whitmer is marrying two issues that must be addressed; one, her concern for the safety of the Great Lakes, and two, the fact that Michigan uses 20.5 million gallons of oil a day. The kicker: Line 5 carries 18.9 million gallons of that.

So it is curious that when a tunnel was proposed with private sector funding and approved by a bipartisan legislative majority to bury the pipeline segment crossing the Strait 100 feet or more below the lakebed, essentially entombing it, Gov. Whitmer and AG Nessel still were not satisfied. The tunnel provided a real, safe solution to provide energy that would not only be reliable but would also help save jobs, safeguard the economy, keep prices low at the pump and most importantly – protect the Great Lakes they vowed to defend. Yet, their campaign promise wasn’t actually to Michiganders, it was to the activist groups.

The problem with aligning with out-of-state activists is fourfold.

First, many don’t live in Michigan enough to care about the people that might be affected by higher prices and lack of access because they are only working to appease the dark money and otherwise anonymous funders for whom they work to stay employed.

The second is the actual economics. Pipelines are built by pipeline companies who contract space within their line to oil companies to transport their product, similar to how networks like Verizon sell service providers bandwidth to connect communities with the internet. These are done through long-term contacts since they’re dealing in bulk commodities that require long-term investments. They don’t physically own the oil or energy products they are moving. They just provide the space and transportation service.

Plus, building pipelines is a very capital-intensive undertaking, and the long-term contracts that these companies require help justify the upfront financing and investment. That’s why oil companies sign contracts for several years, even decades, which guarantees they will move their product on that line over that time period. However, because of the amount of oil pipelines can move, they are not only considered the most efficient but also the most cost-effective. The longer the contract, the cheaper the rate of transportation can be. It’s kind of like buying in bulk at Costco.

The rule of thumb is that pricing and efficiency go down by different modes of transportation based on the volume they can move per day. So pipelines take the top spot, a ship or barge follows, then train and finally – truck. The trucks you see on the road, perhaps going to your gas station, are only taking fuel the last few miles.

Also, in bulk commodities like oil, roughly 80% of the delivered cost of that barrel is from transportation to the refinery where it is priced at the intake valve. So if you can keep delivery costs low with longer contracted rates, it’s better. By canceling a pipeline, it doesn’t mean you can just add oil on another line, take another company’s place or re-route an existing line. It’s why you can’t rent an occupied apartment – until the paying tenant’s lease is up and they decide to leave, you can’t move in and sign your own lease. Remember, these long-term contracts take years to realign and the oil in those lines is often already spoken for and there may not be additional space on another line.

Third, there is no real logistical equivalent to a pipeline. The alternatives like a truck or railcar are no match for pure capacity, safety or emissions. It’s estimated that it would take 2,100 trucks heading east every day – or 90 trucks an hour – leaving from Superior and traveling across Michigan, or roughly 800 railcars to do the same job. To do this, it would also require the state of Michigan, which is notorious for its damaged highways, to develop roads and rail lines that would be able to handle the increased traffic. Then there is the question of who pays for the train tracks since they don’t have the same state-federal funding that roads already do.

Then you’ll need enough of the specialty trucks and railcars that are certified to carry hazardous materials and assume you’ll have enough drivers in the middle of a truck driver and commercial driver’s license shortage across America. These modes of transportation also rely on fuel to power their engines, which actually leads to higher greenhouse gas emissions, according to the latest study by the Energy Information Administration. It’s ironic since the stated goal of Gov. Whitmer and AG Nessel is to protect the environment. Federal data also confirms that pipelines are the safest way to move the oil our economy relies on every day, so using other modes of transit-only increases the potential risk of a spill into the environment. Yet, their craven support for shutting down Line 5 actually flies in the face of our country and Michigan’s shared goal of reducing carbon emissions. It may be the reason they give, but the fact that they continue to brush off these consequences in defiance tells us something else is motivating the governor and her AG.

It’s no surprise since activist goals are almost always about stopping something and rarely align with the bigger picture or more realistic solutions to the problem they point to. It’s always full ahead stop, and damn the torpedoes.

Lastly, and most importantly are the distinctions in how crude oil is refined. When people talk about oil, it is important to know that there isn’t just one type. Crude oil is a general term to describe all varieties of oil, but there are essentially four main types of oil – very light, light, medium, and heavy oils. Depending on what type of oil is being transported, a specific refinery will be needed. The crude oil transported on Line 5 is light oil. The refineries it is sent to process light oil. You can’t just bring in oil from another line if it doesn’t match up. Similarly, you wouldn’t put water and flour in a Ninja blender or an apple in a mixing bowl – their intended use has been skewed. Not to mention, the refineries also have set contracted rates that come into play.

These refineries also run 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, and require a large number of

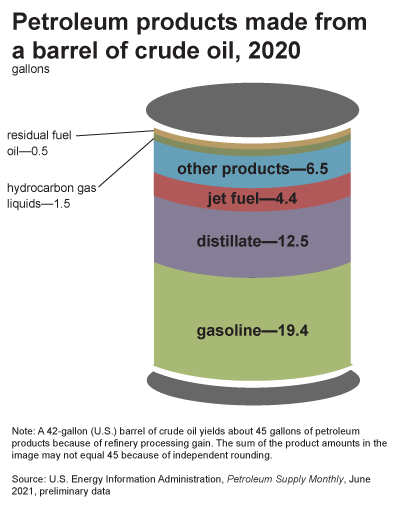

employees to produce on average, from a 42-gallon barrel of crude oil, roughly 19 to 20 gallons of motor gasoline; 11 to 13 gallons of distillate fuel most of which is sold as diesel fuel; 3 to 4 gallons of jet fuel; and other byproducts, according to the Energy Information Administration.

Refineries are also not located in every city, they’re spread out across the U.S., with the largest number of them centered in our nation’s refinery complexes. You can see where they are all located here at the Visual Capitalist in their interactive crude oil and refinery infographic.

The Nightmare

Many of the solutions that have been suggested by these out-of-state activists will take time and lots of money. Both of which won’t alleviate the problem for some time and don’t account for the continued demand for gasoline and jet fuel. With roughly 2,691,704 registered vehicles on the road in Michigan and 1,100 flights per day out of Detroit – that’s a lot of fuel to bring in. While the prices we’re seeing now will go down, adding in a supply deficit would make them go back up.

Our latest economic study on fuel prices showed that families and businesses in Michigan and across the Midwest would spend at least $23.5 billion more on gasoline and diesel – a 9.5 – 11.7% increase in fuel prices over the following five years. That increase also gets passed on to food production and products, which increases the cost of everything by one-third. We’re already living through what happens when there is a shortage of fuel, and seeing its effects on literally every part of our economy. Is that really what we want to do to people in Michigan – especially now?